Colonial education and its wider economic, social and cultural extractive tendencies had an enduring damaging effect on Zimbabwe’s educational system design.

This laid the groundwork for inequalities in the economic, social, cultural, scientific and technological structures we not only see in Zimbabwe but in most African countries as a whole.

A number of studies of the British Empire and its enduring legacies over the years have unearthed and untangled the complexities of historic injustices to inform and shape Zimbabwe and Africa’s scientific, innovation and technological movement.

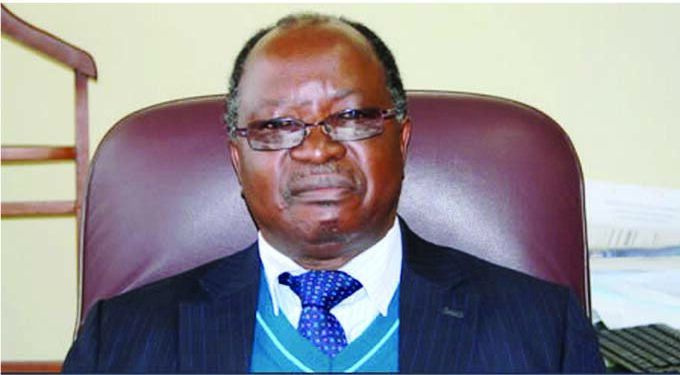

Renowned scholar and metallurgical engineer, Professor David Simbi, who is also the Vice Chancellor of Chinhoyi University of Technology in his latest book: Zimbabwe’s Education Systems Design: An Imperial Bequeathment — ‘A Blessing or Curse’, tackles African pre-historic and pre-colonial ingenuity, colonial education, the post-independence education system up to the new Education 5.0 which was crafted to reconfigure the country’s education system from a colonial one into a new one that is really Zimbabwean and African.

His book lays an important ground by laying bare the colonial educational, economic and social injustices that he argues, led to the obliteration of African thought culture and worship and its replacement with western culture and Christian devotion |through a master-minded education architecture that has had enduring consequences.

The Chinhoyi University of Technology scholar’s book is very critical in understanding the history of the education system in Zimbabwe and why, under the Second Republic the adoption of Education 5.0 which focuses more on problem-solving through innovation is vital for the Fourth Industrial Revolution which is expected to accelerate Zimbabwe’s industrialisation and modernisation thrust.

It is amazing how Prof Simbi, mixes his personal experiences — life history to expose the bad reverberations of the influence of the British colonialism and the search for an inward looking and Pan African education system that appreciates the value of indigenous knowledge, African pre-colonial ingenuity and other social and economic achievements.

The narrative is carefully calibrated and well-structured to appeal not only to the academia but to anyone who seeks to understand Zimbabwe’s pre-colonial knowledge systems and achievements, the damaging and enduring effects of colonial education systems as well as the rise of the new Education 5.0 school of thought on the country’s educational pathways.

To begin with, Prof Simbi recalls his childhood and how his young mind tried to break through the rigid Rhodesian educational system and its rough-edged inequalities.

He traces his rise from a colonial farming compound at Peter de Kok’s white settler farm in Nyazura, his primary education at Dowa Primary School during the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland years, high school years at Nyazura Mission and Solusi Mission where he completed his O-level education in 1971 up to the time he left the country to study in the UK.

Prof Simbi remembers how the late hero Professor Phineas Makhurane, who was a recruiting officer for Zimbabwe’s liberation movement Zapu in Botswana, helped him secure a scholarship to study in the UK from 1974.

At this time, he saw first-hand the colonial injustices and encountered African scholars who were already deep into the African resistance to colonialism.

“It is therefore not possible for one to discuss the architecture, system or formulation of education in Zimbabwe without perhaps briefly examining the origins of learning processes that embrace the rite of passage traditional rituals whose genesis dates back to early kingdoms of antiquity and were ignored in subsequent developments in education to the current state.

“In order to further understand the bigger picture, the question must be asked whether the introduction of western education by missionaries and colonial administrators was in itself a benevolent act designed to redeem the African race from the dark age, or rather it was part of the bigger plan devised to facilitate empire building to support the commercial trade that emerged subsequent to the first industrial revolution in the 18th century Europe spreading to the Americas.”

The CUT scholar digs deep into the past tracing history and using his personal experiences and of others during his formative years to analyse issues pertinent to the formal education design by British colonial administrators in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Using the example of the Munhumutapa State and the Great Zimbabwe Monument, Prof Simbi notes that Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) embedded in Africa’s cultural heritage were destroyed, denigrated or marginalised and replaced with Western views and approaches to serve the interests of European settlers.

In his book, like many other Pan African scholars before him, he argues that without slavery and colonial subjugation, Africa’s story of scientific innovation and technological advancement would have been different today.

His works makes one to appreciate one of the unmistakable stamps of ingenuity and technological prowess by our ancestors that included the impressive Great Zimbabwe National Monument and similar sites like Danamombe, Naletale, Khami, Ziwa and Shangagwe between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers.

Zimbabwe’s priceless dry-stone walled monuments provide useful insights into the scientific and technological achievements of early Africans whose role in the development of science worldwide has been side-lined.

Scientific knowledge and modern technologies are largely produced in the industrialised North and consumed by the global South. Africa’s productivity in science, technology and innovation today ranks among the lowest globally. This has hardened negative perceptions about Africa.

“At independence there was a heightened desire to create an education system that acknowledged religious seal and an appreciation of missionary efforts and move towards African emancipation: a shift away from life of toil to participate in creative thinking that applied art, science, technology, innovation and engineering to produce goods and services based on a well-defined western culture and heritage philosophy.

The question for which we all seek answers is whether the inherited colonial education, a standard in all former British colonies has been able to deliver on this promise.”

In his new book, Prof Simbi says we must not lose sight of outstanding contributions to global STI development by Africans. There is vast talent and innovation in the country, but negative perceptions, self-denial and lack of confidence remain major stumbling blocks.

The essence of this book: “Zimbabwe’s Education Systems Design: An Imperial Bequeathment – ‘A Blessing or Curse,” is to help appreciate that Zimbabwe’s rich heritage provides a basis for national identity, scientific and historical research, sustainable tourism, and other economic development opportunities for future generations.

It’s a must read for anyone who wants to understand how Zimbabwe came to adopt Education 5.0 which focuses more on problem-solving through innovation to accelerate Zimbabwe’s industrialisation and modernisation thrust. – Sunday News