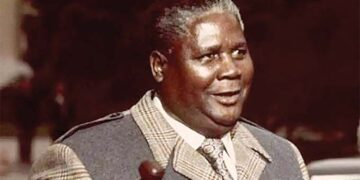

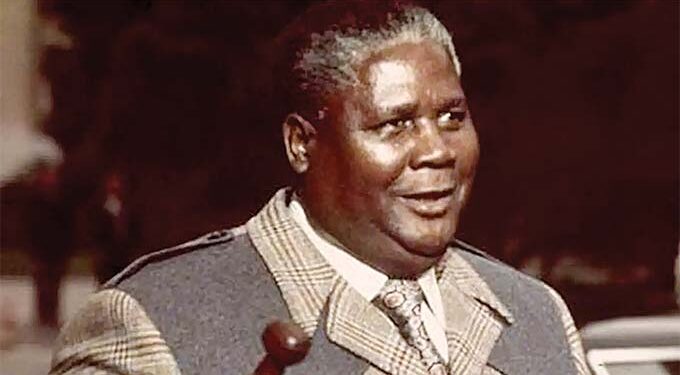

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo, affectionately known as Father Zimbabwe is decidedly one of the most influential shapers of Zimbabwean history whose enduring charisma and stage presence became a major source of inspiration for the country’s struggle for independence.

He was a towering political figure whose importance in the 20th century for Zimbabwe and Africa far outweighed sentiments from his Rhodesian enemies.

Every year, on July 1 — the day he died (July 1, 1999) fills Zimbabweans and most Africans with powerful emotions, recalling the countless ways in which Father Zimbabwe altered the course of individual lives, people and the entire Zimbabwean nation.

History has recorded and judged his enormous impact on the people of Zimbabwe and the world as a whole.

Nkomo’s story is a story of how the very idea of being Zimbabweans is intimately linked to the idea of freedom, a connection that was amplified by his involvement in the struggle against British colonialism.

His momentous story of the struggle for freedom is still relevant not only for a new generation of Zimbabweans but also for all those engaged in emancipatory struggles internationally.

The supreme sacrifice made by him and other comrades earned us the freedom we enjoy today and the opportunity for economic development that the country presents.

Zimbabwe and Africa continue to commemorate the life achievements of Cde Nkomo and other heroes so as not to forget their supreme sacrifices and how they inspired and influenced Zimbabwe’s political landscape.

In a statement to commemorate the 24th anniversary of his death, President Mnangagwa aptly captures the story of the life of Cde Nkomo — one of the greatest symbols of freedom, black —empowerment, unity and the struggle for land.

President Mnangagwa remembers Cde Nkomo’s strength and symbolism in the country’s liberation struggle.

“Today, 1st July, 2023, our great nation, including our brothers and sisters in the Diaspora, joins the Nkomo family in remembering the late national hero, Dr Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo, on the 24th anniversary of his death.

“Dr Joshua Nkomo served as Vice-President of the Republic of Zimbabwe from 1987 until his untimely demise on 1st July, 1999.

“The late former Vice-President, affectionately known as “Chibwechitedza”, “Umdala Wethu”, “Father Zimbabwe”, was a trade unionist, a revered nationalist and a Pan-African freedom fighter who committed his entire adult life to the decolonisation and emancipation of the people of Zimbabwe,” he said.

“The memories of this doyen of African liberation, a gentle giant and a passionate nation-builder, shall forever be etched in our hearts.”

Nkomo was a fiery apostle of the revolution and right from the beginning of the nationalistic struggle, he said that return of the land to the majority was central to their cause: “What will be the future of the people’s land?” he asked the British at the Lancaster House talks.

During the struggle and after independence, Nkomo was vocal on land and black empowerment issues.

In 1980 he devised a plan to buy party houses, office buildings and farms in an effort to transfer wealth from white colonial rulers to indigenous blacks.

All this was part of his strategy to ensure that former freedom fighters and the masses benefited from the liberation struggle following a 16-year brutal armed war that claimed thousands of lives.

For several centuries, land and politics were deeply intertwined in Zimbabwe.

The loss of land by the majority of the people was at the centre of the liberation struggle. Land was an emotive issue that forced blacks to take arms to fight for it.

Blood was sacrificed for land. Thousands of people lost their lives for the liberation of the country. In essence, they lost their lives for the land called Zimbabwe.

In 1979, at the Lancaster House talks, an equitable redistribution of land for the landless people was sought without damaging the white farmers’ vital contribution to Zimbabwe’s economy that accounted for some 40 percent of exports and provided a livelihood for over 30 percent of the paid workforce while generating 80 percent of the country’s total agricultural output.

Land Reform in Zimbabwe was at the centre of the Lancaster House Agreement, with the British and the Americans making several concessions to support it, in return for peace and security for their own kith and kin.

Nkomo and his colleagues in Government stood firm despite the imposition of sanctions, which are still in place even up to now, to implement the Land Reform Programme.

It was a necessary commitment to alleviate overpopulation in the former tribal trust lands (TTLs — now known as communal areas) to extend the production potential of small-scale subsistence farmers, and improve the standards of living of rural Zimbabweans.

It was an epitome of correcting historical wrongs, social injustice and economic inequalities of the past.

Some 4 500 white farmers who occupied nearly 70 percent of Zimbabwe’s fertile and rich lands were dispossessed and a million black Zimbabweans were resettled.

His vision for unity, for land equity, social, economic and political rights, can be found by looking not to the future but to the past in which his visionary and influential political role shaped the country’s nationalistic politics.

Nkomo’s legacy cannot be wished away. It’s part of us and we walk with it in every Zimbabwean way.

Hewas Zimbabwe’s foremost nationalist figure who played a critical role in bringing about not only the country’s independence, but national healing and reconciliation among Zimbabweans after the political disturbances of the early 1980s.

His legacy in terms of unity, national healing and reconciliation is still enduring.

Thoughts about his life, his stature, his unifying role, his bold and unyielding fight for land, social, political and economic rights for the majority of blacks should inspire us and the young generation about how his life and sacrifice impacted on our lives.

The name Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo should inspire some reasoning, upliftment and sharing of perspectives about thefuture discourse of our country’s national politics.

He was a man of the people who taught this nation the importance of unity and the value of the struggle for land in shaping us as a nation.

On the whole, the commemoration of his death on July 1 should inform all generations in this country of their history and why it is important to keep up with current situations which also still require Nkomo’s great message of peace and national reconciliation.

And no matter the differences that we may hold as a people, it is still very important to preserve Nkomo’s legacy.

“Father Zimbabwe will be remembered as a colossal political figure who, together with his compatriots, gallantly fought and defeated racial injustice, oppression and servitude,” President Mnangagwa said.

“He belonged to an early crop of trade unionists who spurned subtle politics for a full-fledged armed struggle in seeking to liberate their motherland.

“Father Zimbabwe left a huge footprint on the Zimbabwean political landscape, an enduring legacy of peace and the lofty values of Unhu/Ubuntu.

“Despite prolonged political incarceration, Dr Nkomo never compromised on his revolutionary ideals, and served as the inaugural Minister of Home Affairs in the newly Independent Zimbabwe in 1980.

“He laterascended to the post of Second Secretary of Zanu (PF) and Vice-President of Zimbabwe in 1987, following his role as co-architect of the historic Unity Accord which was signed on 22nd December, 1987.”

The veteran nationalist was born on June 19, 1917 at Semokwe in Kezi District, Matabeleland South.

He was the third born child in a family of eight.

His father Thomas Nyongolo Letswansto Nkomo was a teacher and lay preacher who was trained and worked for the London Missionary Society.

Nkomo was a founding leader of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu) and worked with numerous other nationalists in the struggle for the liberation of Zimbabwe.

After primary schooling in Rhodesia, he went to South Africa to complete his education in Natal and Johannesburg. Returning home in 1945, he worked for the Rhodesia Railways and by 1951 had become a leader in the trade union of the black Rhodesian railway workers. In 1951 he obtained an external BA degree from the University of South Africa, Johannesburg.

Nkomo became increasingly political, and in 1957 he was elected president of the African National Congress (ANC), the leading black nationalist organisation in Rhodesia. When the ANC was banned early in 1959, Nkomo went to England to escape imprisonment.

He returned in 1960 and founded the National Democratic Party (NDP) in 1961, when the NDP was banned in turn, he founded Zapu.

The white-minority government of Rhodesia held Nkomo in detention from 1964 until 1974. After his release he travelled widely in Africa and Europe to promote Zapu’s goal of black majority rule in Rhodesia.

Nkomo helped lead the guerrilla war against white rule in Rhodesia alongside Robert Mugabe, who headed the Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu) after the ouster of Ndabaningi Sithole.

The two groups were joined in an uneasy alliance known as the Patriotic Front after 1976.

When the country gained independence in 1980, there were serious differences between Nkomo and Mugabe which culminated in political disturbances.

After resolving their differences, they agreed in 1987 to merge their respective parties to bring unity and peace in Zimbabwe.

The signing of the Unity Accord on December 22, 1987 led to the end of the civil unrest and brought unity to the country. It was historic.

In 1990, Nkomo became Vice-President and played a critical role in shaping the country’s social and economic development.

In 1996, Nkomo was diagnosed with prostate cancer. His deteriorating health forced him to retreat from public life, although he continued to hold office until his death in 1999.

He died on July 1, 1999, leaving behind a solid and rich legacy of the nationalist struggle, peace and unity.

Nkomo was laid to rest at the National Heroes Acre on July 5, 1999 where an estimated 100 000 mourners thronged the shrine to pay their last respects.

Father Zimbabwe or Chibwechitedza’s legacy lives on. – The Chronicle